My first day of “retirement”, I took the Trifecta to school, ran some errands and then wanted to get out. It was a cold, windy day, with intermittent snow showers, but no real accumulation- bad for biking, not great for skiing- so I went for a hike. I talked Awesome Wife- who’d just come home from work*- into tagging along as far as the zoo, where she kissed me goodbye and turned back while I crossed Sunnyside Ave. and started climbing.

*Yes, work. Ironically, the week I stopped working was the week she started working. It’s not what you think. AW was a half-time reading specialist in a local elementary school last year, but her contract wasn’t renewed this year due to lack of funding. The recent influx of federal education money enabled her school to re-hire her. She’s thrilled.

Tangent: I had my first “retired moment” Wednesday. SkiBikeJunkie and I took a long lunch to ski up in Little Cottonwood Canyon. We were late getting back and SBJ had to run back to work. I had a couple of errands to run, but I was hungry, and stopped into a local Barbacoa to grab a burrito, which, as usual, I planned to take with me. But as I was walking away from the counter, I realized that I didn’t have to be anywhere, and I stopped and ate right there, while leafing through one of the local alternative papers. It was both cool and kind of weird…

Most of this project has occurred in and around the Wasatch Mountains, and the lion’s share of the trees, birds, shrubs, mammals, mosses, lichens and other things we’ve looked at are here because of this massive 11,000 foot-high wall in my back yard. For that matter, it’s why I’m here. The wall of the Wasatch, and the perennial water source it provides, is the reason why the Utes camped by the shores of Utah Lake, why the Mormon pioneers stopped here, and why it harbors one of only two major cities* in the Great Basin. Before wrapping up the project, we should probably have some idea why the Wasatch is here, how it came about, and why it is the way it is.

*Reno is the other.

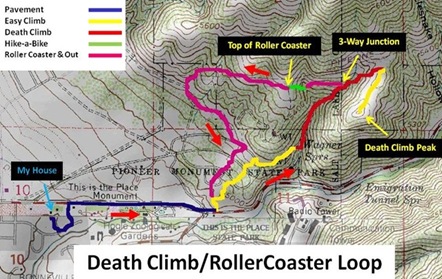

I quickly reached the top of the Roller-Coaster and continued climbing up the faint trail leading North. The trail is steeper here, but it was cold enough to more or less hold the mud together and provide solid footing.

I quickly reached the top of the Roller-Coaster and continued climbing up the faint trail leading North. The trail is steeper here, but it was cold enough to more or less hold the mud together and provide solid footing.

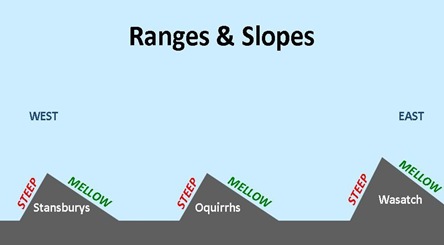

Throughout this project, huge numbers of the things I’ve blogged about, especially in Spring, have been located in what  I’ve generally referred to as the “foothills.” But the West slope of the Wasatch doesn’t really have “foothills” in the strict sense. For the most part, the West slope of the Wasatch is characterized by high peaks rising dramatically from the valley floor. When I first moved here, this was one of the big surprises. Back in the Denver area (Life 1.0), I lived and recreated mainly in the foothills of the East slope of the Front Range, which gradually work their way up over 20-30 miles to a high crest. But from the floor of Salt Lake Valley to 11,000 foot peaks is only a couple of (crow-flying) miles.

I’ve generally referred to as the “foothills.” But the West slope of the Wasatch doesn’t really have “foothills” in the strict sense. For the most part, the West slope of the Wasatch is characterized by high peaks rising dramatically from the valley floor. When I first moved here, this was one of the big surprises. Back in the Denver area (Life 1.0), I lived and recreated mainly in the foothills of the East slope of the Front Range, which gradually work their way up over 20-30 miles to a high crest. But from the floor of Salt Lake Valley to 11,000 foot peaks is only a couple of (crow-flying) miles.

What’s interesting is that the other side of the Wasatch- the East slope- isn’t like this. It sort of gently tumbles down to Park City and Heber through rolling forested slopes (which is why there’s so much better mtn biking over on that side of the Front.) And what’s even more interesting is that if you check out the next 2 ranges to the West- the Oquirrhs and the Stansburys, they’re set up exactly the same way, with a steep West face and a gentle East slope.

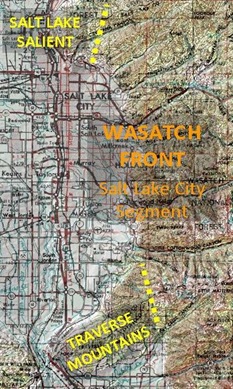

The Wasatch Range- depending on how it’s defined- extends over 200 miles from Fayette, UT to Malad City, ID. Along its course the West-facing front is regularly interrupted by a series of minor East-West protrusions, or “bumps”, that geologists use to break the range up into segments. Our segment, the Salt Lake City segment, is bounded by the Traverse

The Wasatch Range- depending on how it’s defined- extends over 200 miles from Fayette, UT to Malad City, ID. Along its course the West-facing front is regularly interrupted by a series of minor East-West protrusions, or “bumps”, that geologists use to break the range up into segments. Our segment, the Salt Lake City segment, is bounded by the Traverse  Mountains in the South (Point of the Mountain, Suncrest, Corner Canyon) and the Salt Lake Salient in the North. The SL Salient is the whole City Creek Canyon/Ensign Peak/radio towers area, and is composed largely of tertiary conglomerates, which I explained in this post*. The dividing line between the Salient and the Wasatch Front proper is the Rudy Flat Fault, which runs right more or less up Spring Gulch, the next minor draw after Limekiln Gulch** as you follow the Shoreline trail to the Northwest. The SL Salient, this little “aberration”, is my extended back yard, and comprises most of the “foothills” I’ve been blogging about.

Mountains in the South (Point of the Mountain, Suncrest, Corner Canyon) and the Salt Lake Salient in the North. The SL Salient is the whole City Creek Canyon/Ensign Peak/radio towers area, and is composed largely of tertiary conglomerates, which I explained in this post*. The dividing line between the Salient and the Wasatch Front proper is the Rudy Flat Fault, which runs right more or less up Spring Gulch, the next minor draw after Limekiln Gulch** as you follow the Shoreline trail to the Northwest. The SL Salient, this little “aberration”, is my extended back yard, and comprises most of the “foothills” I’ve been blogging about.

*The tertiary conglomerate story in the salient is actually more complicated than I realized at the time of that post. Much of the salient is composed of 2 different conglomerates, which while similar in form, were laid down about 18M years apart. Essentially, over behind the Capitol you’re on what’s called Tertiary Conglomerate 1, which is about 35M years old, but between City Creek and Spring Gulch you’re mostly on Tertiary Conglomerate 2, which is only about 17M years old.

**Which in turn is the minor draw just North of Dry Creek.

Extra Detail: One of the confusing things about major faults to non-geologists is that they involve lots of little faults. For example, another little fault- the Warm Springs Fault- defines the Western edge of the SL salient, and it’s what you drive along when you take 89 up to Bountiful. For that matter, you have a bird’s eye view of another minor (unnamed) fault from the top of the Roller-Coaster, which runs right up the Death Climb gulch.

The steep pitch above the Roller-Coaster only lasts for 5 or so minutes before you reach what I call The Shoulder, a short, open ridge that’s a perfect spot for a picnic or a nap on a Spring day. On this day though the wind was whipping and I donned sunglasses to protect my eyes from the sideways graupel*.

The steep pitch above the Roller-Coaster only lasts for 5 or so minutes before you reach what I call The Shoulder, a short, open ridge that’s a perfect spot for a picnic or a nap on a Spring day. On this day though the wind was whipping and I donned sunglasses to protect my eyes from the sideways graupel*.

*Apparently, that is how you spell it. I never knew till I had to look it up for this post.

In 1995 when I moved to Utah, my first job was located in an old 3-story office building in downtown Provo. I remember one afternoon we had a visitor who my boss was showing around. As they looked out the window he pointed out Mount Nebo to the South, the highest peak of the Wasatch, and described it as the “last of the Rockies.” I loved that- the last of the Rockies. For years afterward, when I’d spot Nebo from afar, or drive past it on I-15, his words would echo in my head- the last of the Rockies… It was more than a decade until I learned he was completely wrong.

The Wasatch certainly seems like the last of the Rockies, and biologically it’s a fair description; the trees, birds and mammals are, for the most part, trees, birds and mammals you can find clear across to Denver. But geologically they’re something completely different and much newer. Rather than the Westernmost range of the Rockies, the Wasatch are the Easternmost range of the Basin and Range province. Between Salt Lake and Reno, range after range- something like 200 of them, almost all running North-South- are separated by wide open valleys. Some of the ranges- like the Cedar Mountains- are low and scrubby. Others- like the Deep Creeks and the Rubies- are high and mighty like the Wasatch. But high or low, the vast majority of them- like the Wasatch, the Oquirrhs and the Stansburys- have one steep side and one gentle side. What’s going in this part of the country?

The Wasatch certainly seems like the last of the Rockies, and biologically it’s a fair description; the trees, birds and mammals are, for the most part, trees, birds and mammals you can find clear across to Denver. But geologically they’re something completely different and much newer. Rather than the Westernmost range of the Rockies, the Wasatch are the Easternmost range of the Basin and Range province. Between Salt Lake and Reno, range after range- something like 200 of them, almost all running North-South- are separated by wide open valleys. Some of the ranges- like the Cedar Mountains- are low and scrubby. Others- like the Deep Creeks and the Rubies- are high and mighty like the Wasatch. But high or low, the vast majority of them- like the Wasatch, the Oquirrhs and the Stansburys- have one steep side and one gentle side. What’s going in this part of the country?

On The Shoulder I pulled my shell out of my pack and put it on. I hate climbing with all my layers on- it means I’ll be cold up top. I followed The Shoulder to its “base” and started climbing again- even more steeply than before, but up here the ground was frozen hard, and the footing easy.

On The Shoulder I pulled my shell out of my pack and put it on. I hate climbing with all my layers on- it means I’ll be cold up top. I followed The Shoulder to its “base” and started climbing again- even more steeply than before, but up here the ground was frozen hard, and the footing easy.

I’ve mentioned Reno a couple of times. If you’ve lived on the Wasatch Front for a while, chances are you’ve had to drive there at some point. And no matter how interesting the geology and botany of the ranges in between, it is a long, boring drive*. And it’s getting longer every year. No really, I mean it: in the last 17.5 million years, the distance between Salt Lake and Reno has nearly doubled.

*On I-80 it is, anyway. I still maintain (even though no one ever agrees with me on this) that driving it over a couple of days on US50 makes for an awesome road trip, which I described in this post, this post, this post and this post.

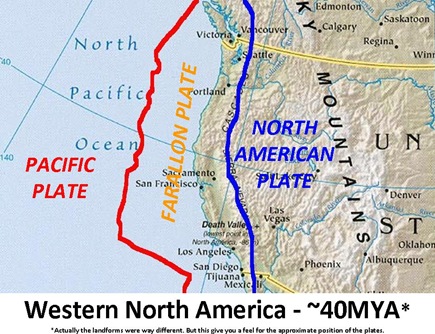

For the last 17.5 million years the Great Basin has been stretching and thinning. The reasons for this are not completely understood, but are believed to be intimately bound up with what’s going on in California. The San Andreas Fault marks where the North American and Pacific crustal plates meet up. But before ~17 million years ago, there was another plate- the Farallon- in between the two. Between ~150 million and ~17 million years ago the Pacific and North American plates gradually worked their way closer together, and as they did so, pushed the Farallon plate down under- or subducted beneath- the North American plate.

During the last 17 million years the San Andreas Fault has been zippering its way Northward, closing the gap with the North American plate and eliminating the Farallon. A small remnant of the Farallon- the Juan de Fuca plate- still exists up around Oregon and Washington, where its ongoing subduction is driving the volcanism of the Cascade Range.

During the last 17 million years the San Andreas Fault has been zippering its way Northward, closing the gap with the North American plate and eliminating the Farallon. A small remnant of the Farallon- the Juan de Fuca plate- still exists up around Oregon and Washington, where its ongoing subduction is driving the volcanism of the Cascade Range.

Extra Detail: Interestingly, the ~20 million year period before 17 MYA was marked by significant and dramatic volcanic activity in the Intermountain West. And following up on the “The reasons for [the Great Basin extension]… not completely understood…” comment, there are at least 5 (probably more) proposed explanations I’m aware of. The topic is too wide-ranging for this post, but an excellent summary of the leading hypotheses can be found in Chapter 12 of Bill Fiero’s Geology of the Great Basin.

Since the zippering began, the Great Basin has been stretching. Currently any given point on the floor of the Salt Lake Valley is creeping Westward at about 2mm/year. Over by Wendover it’s stretching faster, more like 3mm/year, and way out in the Black Rock desert in Northwest Nevada the ground is moving at something like 8mm/year. As it stretches, it’s also thinning. Nevada and Utah’s West Desert are sprinkled liberally with geothermal hot springs and evidence of recent volcanic activity, such as the Tabernacle Hill area West of Fillmore.

Since the zippering began, the Great Basin has been stretching. Currently any given point on the floor of the Salt Lake Valley is creeping Westward at about 2mm/year. Over by Wendover it’s stretching faster, more like 3mm/year, and way out in the Black Rock desert in Northwest Nevada the ground is moving at something like 8mm/year. As it stretches, it’s also thinning. Nevada and Utah’s West Desert are sprinkled liberally with geothermal hot springs and evidence of recent volcanic activity, such as the Tabernacle Hill area West of Fillmore.

All About Southern Idaho

I’m including this side note because a) it’s vaguely related to the geology we’re discussing, b) I meant to blog about it last summer but never got around to, and c) Southern Idaho generally gets a bum rap as mega-boring (which it kind of is) but its geology is fantastic.

Side Note: Another recent spectacular example of such activity is Southern Idaho, which has tons of volcanic features, such as Craters of the Moon National Monument and Hell’s Half-Acre (pic below, right)*. But Southern Idaho’s volcanic history is more complex than suggested by these features.

*Which is right along I-15 between Idaho Falls and Pocatello. The next time you’re driving this stretch, you absolutely must stop for 30 minutes. It’s the best bang-for-buck quick lava field stop in the contiguous 48 states.

The foundation of the entire Snake River Plain is a series of massive basalt layers laid down in a period of super-volcanism roughly 17.5 MYA. The obvious black lava fields you see at Craters of the Moon  et al are far more recent, only a couple of thousand years old, and have created only a teensy-weensy fraction of the volume of rock produced by the earlier volcanic period. The earlier period is basically Yellowstone. The volcanic and geothermal activity in Yellowstone National Park is the result of a soft, or “weak”, spot in the Earth’s mantle. The reasons for this soft/weak spot are debated (the most exciting hypothesis may be an ancient meteorite impact), but the spot has been in the same place for at least the last 17.5M years. But the Earth’s crust has been moving across it, such that ~17 MYA what is now the Snake River Plain was right on top of it. The “new” stuff is a completely different deal, the stretching/thinning of the Great Basin, and the volcanism produced by it rather inconsequential in comparison. It only looks consequential because it’s so recent.

et al are far more recent, only a couple of thousand years old, and have created only a teensy-weensy fraction of the volume of rock produced by the earlier volcanic period. The earlier period is basically Yellowstone. The volcanic and geothermal activity in Yellowstone National Park is the result of a soft, or “weak”, spot in the Earth’s mantle. The reasons for this soft/weak spot are debated (the most exciting hypothesis may be an ancient meteorite impact), but the spot has been in the same place for at least the last 17.5M years. But the Earth’s crust has been moving across it, such that ~17 MYA what is now the Snake River Plain was right on top of it. The “new” stuff is a completely different deal, the stretching/thinning of the Great Basin, and the volcanism produced by it rather inconsequential in comparison. It only looks consequential because it’s so recent.

Everything you’ve heard BTW about the Yellowstone caldera is true; it blows up spectacularly pretty much once every 600,000 years, we’re due for another go anytime now, and it’s going to suck for us when it blows.

At the top of the pitch above the shoulder I encountered the first real tree- a Curlleaf Mountain Mahogany. I gazed up for years at these strange trees before I knew their cool story: evergreen angiosperms, they’re like the Rose Family’s version of a Juniper. They do so well on these exposed ridges; the scrub-oak here barely manages to grow thigh-high, but the Mountain Mahogany stands high above my head. About 50 feet further up the underlying tilted rocks emerge from the ground in a minor, ridge-defining hogback, which provided some bit of shelter from the wind. I slowed down when I reached it, bending down behind the hogback for cover.

Well, all that’s interesting, but what’s it got to do with mountains? We generally think of mountain ranges forming when crustal plates push up against each other, which intuitively makes sense. The Himalayas are a great example: India runs North, smacks into the soft underbelly of Asia and up crumple K2 and Everest. But why would stretching produce mountains? Why wouldn’t the land just get flatter?

Well, all that’s interesting, but what’s it got to do with mountains? We generally think of mountain ranges forming when crustal plates push up against each other, which intuitively makes sense. The Himalayas are a great example: India runs North, smacks into the soft underbelly of Asia and up crumple K2 and Everest. But why would stretching produce mountains? Why wouldn’t the land just get flatter?

The hogback, along with all the underlying rock on Wire Peak, is Twin Creek Limestone, a light-gray marine limestone laid down in the Jurassic. It’s abrasive, high-friction and generally makes for good hand/toeholds, but fractures easily; when scrambling on it you have to “test” each chunk before committing your full weight to it. Perkins Peak, the next peak South*, is also Twin Creek, but none of the other peaks in this area are. Red Butte, the next peak North, is composed of a completely different rock- the reddish Nugget Sandstone, and the peaks to the South composed of still different formations.

*Hardly anyone ever climbs it. I’ve done so twice, and it’s a cool hike, though you have to be patient threading your way through the scrub-oak. Easiest way is to park at Little Mountain Pass and start walking West along the ridge.

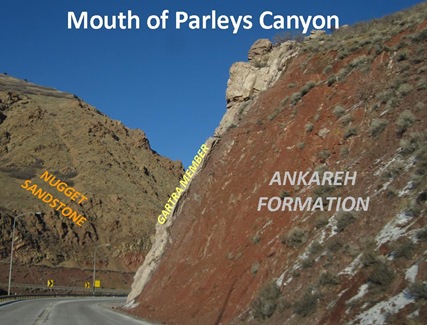

Extra Detail: I described the geology of Mill Creek Canyon in this post. Parleys Canyon BTW has awesome geology you can check out from the car window. As you drive along the ramp connecting I-215 Northbound to I-80 Eastbound, you pass alongside a wall of reddish rock- the Ankareh formation. Suddenly, just before you enter the canyon, you’ll pass a band of white rock tilted at about 70-80 degrees, This is the Gartra Member of the Ankareh formation and there are 2 really cool things about it.

The first is that if you turn your head and look left/down, you’ll see that the member extends down to “Suicide Rock”, the heavily-painted outcrop at the mouth of Parleys. And if you pay attention from down in the valley, you’ll see that the white line of the Gartra extends clear up in a well-defined hogback to the North “shoulder” of Grandeur Peak. All of that, from Suicide Rock on up, is the same band of rock.

The first is that if you turn your head and look left/down, you’ll see that the member extends down to “Suicide Rock”, the heavily-painted outcrop at the mouth of Parleys. And if you pay attention from down in the valley, you’ll see that the white line of the Gartra extends clear up in a well-defined hogback to the North “shoulder” of Grandeur Peak. All of that, from Suicide Rock on up, is the same band of rock.

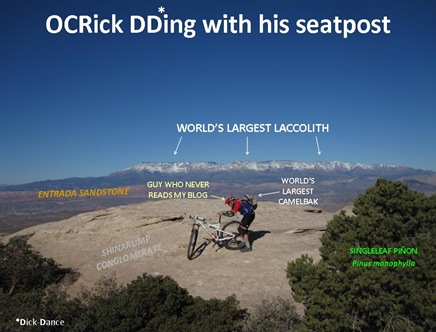

The second cool thing is that the Gartra is chronologically and sequentially analogous to the Shinarump Conglomerate* of Southwest Utah. So essentially, that white band of rock running up from the mouth of Parley is our own little Wasatch version of Gooseberry Mesa, except that it’s titled nearly 80 degrees on its side!

*Which we looked at in this post. Man, it is like I have a post for everything.

The Great Basin ranges aren’t formed via “crumpling”, but through a process called “fault-blocking”. Essentially as minor pieces of the Earth’s crust are pulled apart, they tilt. As the chunks of crust tilt, they form breaks, or faults, where the edge of the tilted block rises above the adjacent block. These tilt-faults become the steep sides of Great Basin mountain ranges. The “mellow” sides of the ranges are the old “tops” of the now-tilted blocks.

You see this pattern all over the Great Basin- one steep/faulted side, one mellow-tilted side. Most of the ranges around here- the Wasatch, Oquirrhs, Stansburys, Cedars- are faulted on the West side, but there are plenty of big ranges- like the Rubies and the East Humboldts faulted on the East.

You see this pattern all over the Great Basin- one steep/faulted side, one mellow-tilted side. Most of the ranges around here- the Wasatch, Oquirrhs, Stansburys, Cedars- are faulted on the West side, but there are plenty of big ranges- like the Rubies and the East Humboldts faulted on the East.

Extra Detail: The easiest-to-see close-by East-faulted range is probably the Canyon Range. Next time you’re headed down to St. George, check out the mountains directly West of Scipio*. Those cliffs to the West are the East slope of the Canyon Range.

*Two years ago I discovered that a) the town is not named for the Roman general but rather for an Indian (who I presume was named for him), b) the “c” is silent, just like with the general, and c) the Chevron cashier/clerk knew all about the Second Punic War, which, I will admit, surprised me.

But I believe the closest West-faulted Range to Salt Lake is- get ready for it- the Newfoundland Range, which coincidentally was the first range I ever blogged about.

But I believe the closest West-faulted Range to Salt Lake is- get ready for it- the Newfoundland Range, which coincidentally was the first range I ever blogged about.

Beyond the hogback the route  passes through an open little mini-woodland of Mountain Mahogany. This is usually an easy stretch, but it was covered with crusty windblown snow concealing old icy footprints beneath. The footing was slow and treacherous, the wind howled, the graupel stung my cheeks, and I wished I’d packed a couple more layers.

passes through an open little mini-woodland of Mountain Mahogany. This is usually an easy stretch, but it was covered with crusty windblown snow concealing old icy footprints beneath. The footing was slow and treacherous, the wind howled, the graupel stung my cheeks, and I wished I’d packed a couple more layers.

Finally I passed between the old signal  panels and trudged up the last slope to the peak. I’ve climbed Wire Peak probably a dozen or so times, sometimes alone, sometimes with kids, a couple of times with a baby on my back. I sat down long enough to strap yak-trax to my boots, gaze West for a moment, then started down.

panels and trudged up the last slope to the peak. I’ve climbed Wire Peak probably a dozen or so times, sometimes alone, sometimes with kids, a couple of times with a baby on my back. I sat down long enough to strap yak-trax to my boots, gaze West for a moment, then started down.

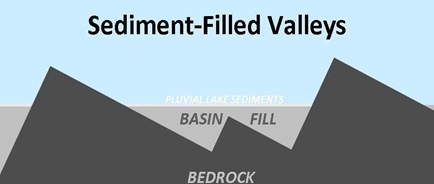

Fault-blocking is a neat story, but when you think about it for a bit there’s something wrong with it- the valleys. They’re wide open and (mainly) flat. Why aren’t they tilted? Because they’re filled with sediment. If you know something of the recent history of Salt Lake Valley, you may think “lake” when you think of sediment.

But the sediments left behind by ancient Lake Bonneville (and Lake Lahontan in the Western Great Basin), though often hundreds of feet thick, constitute only a thin veneer over the deeper, thicker sediments, which are the product of 17 million years of erosion-rubble. As the blocks have faulted and tilted, rains, streams and gravity have worn away at them, filing the basins with rubble. Near my house on the East side of the valley, the rubble, or Basin Fill, is only about 600 feet deep. But out by the refineries in North Salt Lake, the fill is 4,000 feet deep. So the Wasatch would stand nearly 11,000 feet above the floor of Salt Lake Valley, if only someone would clean out the rubble.

But the sediments left behind by ancient Lake Bonneville (and Lake Lahontan in the Western Great Basin), though often hundreds of feet thick, constitute only a thin veneer over the deeper, thicker sediments, which are the product of 17 million years of erosion-rubble. As the blocks have faulted and tilted, rains, streams and gravity have worn away at them, filing the basins with rubble. Near my house on the East side of the valley, the rubble, or Basin Fill, is only about 600 feet deep. But out by the refineries in North Salt Lake, the fill is 4,000 feet deep. So the Wasatch would stand nearly 11,000 feet above the floor of Salt Lake Valley, if only someone would clean out the rubble.

Extra Detail: How can they tell how deep the fill is? There are 3 ways. The first- and by far biggest hassle- is by drilling till you hit bedrock. The second is via seismic soundings. But the cheapest and coolest way is by measuring gravity. Basin fill is less dense than bedrock, so gravity is weaker where fill is thicker, leading to the fascinating corollary that you weigh less at the refineries than you do in say downtown Murray!*

*I had to think about locations here, and could be wrong about this example. You need to equalize for altitude and latitude, both of which also affect surface gravity.

The story is even more dramatic in other valleys. A well drilled in the 1970’s West of Spanish Fork in Utah Valley bottomed out at 13,000 feet. Think about what that means for a moment: The real height difference between the bedrock-valley-floor and the peak of Mt Nebo is about 25,000 feet! The real bedrock-valley-floor of Utah Valley lies more than 8,000 feet below sea level.

The fill-depths of most Great Basin valleys are unknown. But there are low rocky ridges that are nearly submerged, but which would stand as massive sheer ranges if the surrounding fill were removed. It’s suspected that some Great Basin valleys hide entire ranges under their fill.

The fill-depths of most Great Basin valleys are unknown. But there are low rocky ridges that are nearly submerged, but which would stand as massive sheer ranges if the surrounding fill were removed. It’s suspected that some Great Basin valleys hide entire ranges under their fill.

I descended quickly but cautiously, driven by the wind and the cold,  but not wanting to slip and twist an ankle. Finally I passed through the mini-woodland, cleared the snow and found firmer footing on frozen ground. Relaxing a bit, I thought of all the hidden life under the hard icy gravel, the spring-parsleys and balsamroots and phloxes and lupines and grasses waiting to burst forth, and the mental images of their sights and smells took the edge off the cold just a bit. All of those things have stories, many of which we’ve looked at over the course of this project. All of those stories are part of the story of the Wasatch, which in turn is part of the story of the Basin and Range province, which in turn… got me thinking about the project, and the 3 lessons I learned from it.

but not wanting to slip and twist an ankle. Finally I passed through the mini-woodland, cleared the snow and found firmer footing on frozen ground. Relaxing a bit, I thought of all the hidden life under the hard icy gravel, the spring-parsleys and balsamroots and phloxes and lupines and grasses waiting to burst forth, and the mental images of their sights and smells took the edge off the cold just a bit. All of those things have stories, many of which we’ve looked at over the course of this project. All of those stories are part of the story of the Wasatch, which in turn is part of the story of the Basin and Range province, which in turn… got me thinking about the project, and the 3 lessons I learned from it.

Lesson #1

This one should be obvious by now, but is worth repeating: Everything has a cool story. I thought I knew this before I started the project, but I really didn’t. I knew that lots of macro-level biological things had cool stories, like moose and pines and magpies and such, but I was largely ignorant of the amazing stories of things like fungi, moss, lichens and bugs. More importantly, I was ignorant of the stories of non-living things. Not just big, bright things, like the stars and the moon, but things like rocks and water and soil. Everything has a cool story- stories full of wonder and luck, perseverance and probability, joy and despair. You could spend a lifetime learning the million stories of the world. If life ultimately has no meaning, no higher purpose than to learn and know some small portion of these stories, then it is absolutely, wonderfully and fantastically worth it.

Side Note: The #1 topic I wish I’d blogged about in the project but didn’t get around to BTW is soil. It looks so simple, but is amazingly complex and is the primary interface between the organic and non-organic worlds. Dirt makes everything work. Ultimately it brings us forth from the inorganic world, and takes us home to it again at the end, but we’ll get to that in a moment…

Lesson #2

All stories are connected to other stories. Again, much of this is obvious. Pollinator-plant, predator-prey and parasite-host stories are all fascinating though largely obvious examples. But less obvious is the dynamism of the relationships in these stories- how migrations, introductions and climate change the balance and composition of populations, and how floral, faunal and other species sweep across the land again and again like waves.

Less obvious still is the connection between organic and inorganic stories. Some of these, such as the links between altitude, geography, climate and living things are straightforward. Others, like selenium in Prince’s Plume and UV-induced folate damage in Europeans are more subtle. Every molecule of chlorophyll contains an atom of magnesium that was born out of an ancient supernova*. After nearly 3 years at this project, I’ve come to see organic vs. inorganic less as a duality (is it dead or alive?) than as a spectrum (what is a virus?)

*For that matter we are chock-full of it, in our bones, muscles and elsewhere. Most adult humans have about ~24 grams of magnesium inside them, making it the 11th-most common element in the body.

Lesson #3

OK, pay attention, here’s the big one: Stories matter. When I say that you probably think I’m saying they matter because nature is beautiful, or every species is a unique treasure, or we need to be good stewards of the Earth or some such. But I’m not saying any of those things (even though they’re all true.)

I think the truth is that inside the heart and soul of every blogger is a frustrated evangelist. Somewhere down deep we think we have an insight or perspective that would somehow enrich others and better the world if only we could a) put a finger on just what it is and b) figure out how to communicate it. While I’ve tried hard to avoid blatant evangelizing, I’ve generally had an evangelical “message” in the back of my mind which the overall theme of the posts in this blog has supported. But here’s the thing: over the course of the project, my evangelical “belief” (EB), as it were, has changed.

My original EB was pretty simple: the world is full of wonder and amazing stories. If more people saw how amazing and wonderful the natural world really is, then they’d be less concerned with reality TV shows and material goods and trivial work-related stress and housing starts and marginal tax rates and a whole bunch of other things that seem real important but are actually pretty minor and stupid and so maybe they’d be a little happier. And since happier people tend to make the people around them happier, the world would be a little bit better place. That’s it. It’s corny, but it’s what I thought, and I still think it, but it’s not all I think.

Tangent: That’s absolutely true, BTW. The part about happy people making people around them happier. Even if you think everything else I tell you in this post is BS, believe that. I used to have a client who liked to say, “Happy wife, happy life”, and as a veteran of 2 marriages to women at radically different locations on the Spectrum of Happiness, I can tell you it’s spot-on. There’s a worthwhile corollary here: making the people in your life a little happier pays you back in spades.

I walked easily along the shoulder, the wind no longer so strong or icy. As I reached the next pitch down the ground started to soften, but not so much as to make things slippery.

No matter what our take on the world around us, the strictly material world-view leads us to a head-scratcher of a place. If “I” am the sum of the stuff that comprises me, then the here-and now “me” is changing all the time as that “stuff” changes. The “me” who opened the mailbox in the Henry Mountains, or rescued the dog with a face-full of porcupine quills, or dated the girl on the bridge, or rode a motorcycle cross-country, or for that matter started this blog, doesn’t exist anymore. And the “me” writing this post won’t be around to see his kids graduate from college, walk his daughter down the aisle, or dance with his wife at their 50th wedding anniversary.

Tangent: My parents’ 50th anniversary is next year. We plan to throw them a big party. My mom initially resisted, but we finally convinced her with a version of the It’ll-be-the-last-time-to-get-all-your-friends-together-for-a-big-bash-before-they-start-corking-off pitch. Actually, it wasn’t a “version”- that was the pitch. Hey, it worked.

But there’s another way of looking at “me”, and that’s to shake off the old-fashioned, evolution-shaped, parochial view of self. Self isn’t an absolute, it’s a configuration. A configuration that can see and hear and feel and figure out stuff and understand it. A configuration comprised by a small, here-right-now snapshot-portion of the immediate biosphere, which in turn is a little here-right-now portion of the broader organic+inorganic world, which in turn, well… planet->solar system->galactic arm->galaxy->Local Group->universe->everything. There isn’t really an absolute “me” or “you” distinct from the Big-Us-Everything any more than a given wave is distinct from the ocean.

I reached the top of the Roller-Coaster and continued down through the scrub-oak which grew taller now, as tall as me, down to the trailhead and Sunnyside Ave. I crossed the street and started walking home. I’d like to say I spent this time thinking great thoughts, but actually I pulled out my phone and started returning calls I’d ignored ringing on the hike up…

I reached the top of the Roller-Coaster and continued down through the scrub-oak which grew taller now, as tall as me, down to the trailhead and Sunnyside Ave. I crossed the street and started walking home. I’d like to say I spent this time thinking great thoughts, but actually I pulled out my phone and started returning calls I’d ignored ringing on the hike up…

Multiple perspectives of self are all well and good, but the problem with this view is the huge gap in between. At one end of the “you” spectrum there’s the Right-Now-Little-You, which is cool to be, but disconnected from everything, and ultimately seems kind of pointless. On the other end there’s this Big-Everything-You, who/which has no end and is part of everything, but there’s this vast distance between the two. Neither of these “you”s relates meaningfully to your here-and-now day-to-day life. Your grow-up, go-to-school, get-a-job, find-true-love, raise-a-family, figure-out-how-you-are-connected-to-the-world, grow-old-and-complain-about-the-government/your health/your kids life.

That’s where stories fit in. Stories link all things-living and dead- together. They connect the little Right-Now-Little-You to the Big-Everything-You. And in between those two extremes, in the jumble of connections and threads between stories across scale and distance and time, is the “you” that matters- the “you” you obsess over, that your friends care about, your family loves and your mom worries about.

I’m not suggesting that if you start paying attention to the natural world you’ll suddenly understand the meaning of life, and for that matter I doubt there is a simple meaning of life/existence that can be summed up in any kind of sentence, paragraph, scripture or manifesto. But that doesn’t mean that you can’t continually gain more and more insight into the meaning of life. Think of this analogy: let’s say you take a week-long vacation to Costa Rica*. You could visit a couple of locations, but there’s no way you could ever “know” the place in a week. You could return the next year, the year after, and the year after that- maybe you could even move there- but you’d simply never know every town, every beach, every swimming hole, every little forest clearing or hilltop in the country. But whether you visited once or fifty times, no matter what you did, for sure you’d know the place better than if you’d spent the vacation in your hotel room watching TV.

*Which, as it turns out, I’ve visited twice. And yes, I’ll be returning again this year. But not just yet…

If life is a vacation, too many of us spend it in the hotel room. There, that’s it. That’s my evangelical message: Get out of your mental hotel room and start checking out the world, even if it’s just the small bit of it in your backyard. Try to understand some little pieces of it, learn stories, make connections. To know and understand yourself, you have to look outward.

When you can, help others do the same. They’re part of the Big-Everything-You anyway, and their stories touch yours, and the stories of those you care about, over and over again. Your story touches a thousand other stories: your friends and colleagues, your kids, your spouse. Live your life so that everyone else’s story is a little bit richer for having touched yours.

I passed the zoo and hung up with Arizona Steve, turned off Sunnyside into my neighborhood, then up my street. My intention of course- blogging or no- is to keep watching the world wake up for as many years as I’m alive and of sound mind, but of course we can never tell where life will take us. The future is full of unforeseens, of challenges and obstacles that can occupy or divert our attention, focus and goals. But by the middle of your life, after a few decades of noticing the lives and paths of those around you, you get a vague, general idea of where your life may be heading.

I’ll spend a year, maybe more, exploring, “walking the Earth”, and trying to best enjoy time with the Trifecta before they head off into the weird haze of adolescence. After a time I’ll likely turn at least part of my focus once again toward concerns material, whether another position, career or business venture.  The Trifecta will continue to bring us- as all children do- worry and pride, heartache and joy, disappointment and hope, until we somehow manage to more or less “raise” them, and Nathan (Bird Whisperer), John (Twin A) and Julia (Twin B) set off on their own adult lives. Sue (Awesome Wife) and I will fumble along, eventually managing to “retire” for good, enjoying our golden years together for as long as health and good fortune allow, happy in each other’s company, yet each secretly, selfishly hoping to be the first to go, leaving the other to face the last dark years alone.

The Trifecta will continue to bring us- as all children do- worry and pride, heartache and joy, disappointment and hope, until we somehow manage to more or less “raise” them, and Nathan (Bird Whisperer), John (Twin A) and Julia (Twin B) set off on their own adult lives. Sue (Awesome Wife) and I will fumble along, eventually managing to “retire” for good, enjoying our golden years together for as long as health and good fortune allow, happy in each other’s company, yet each secretly, selfishly hoping to be the first to go, leaving the other to face the last dark years alone.

But how and whenever the end comes, I know this one thing: that if I have at least a moment’s clarity before the end, I’ll think that way back when, in the early decades of the century, for at least a few years, I Watched the World Wake Up.

End of Part One

Note About Sources: Info for this post came from Utah’s Spectacular Geology, Lehi F. Hintze, Geology of the Great Basin, Bill Fiero, Geologic History of Utah, Lehi F. Hintze, and Roadside Geology of Idaho, David D. Alt.

![Perseus Andromeda Action Graphic[4] Perseus Andromeda Action Graphic[4]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/_6LWjP0sZ22w/TTkaYHEwa8I/AAAAAAAAJLc/cdRkiUOL6SM/Perseus%20Andromeda%20Action%20Graphic%5B4%5D_thumb%5B2%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)